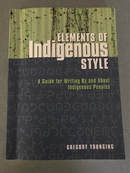

Younging, an author, the publisher at Theytus Books and a teacher of Indigenous Studies at University of British Columbia Okanagan, is also a brilliant storyteller.

He is a member of Opaskawayak Cree Nation in northern Manitoba, has an MA, a MPub and a PhD. Sharing this style guide is just the tip of his expertise iceberg.

A style guide offering urgently needed solutions

In Elements of Indigenous Style, Younging takes the time to explain why this guide is needed. He blends in the literary history of Indigenous Peoples, highlights rights, addresses culturally appropriate publishing practices, provides a terminology guide and introduces specific editorial issues and strategies. Principle 1: The Purpose of Indigenous Style points out the need to reflect the reality of Indigenous Peoples, be truthful in content and be respectful of culture. This is just one of 22 style points presented.

If a style guide is the backbone of the writer’s trade, Younging's guide is the heart and soul of Indigenous publishing. But beware: you will most likely need to give your own style guide a revamp.

New style guide for an old problem

Younging explains how, to date, literature on Indigenous Peoples has focused on information about them rather than from their perspective. Writers need to replace historic styles with new ones that incorporate the Indigenous Voice and incorporate oral, traditional and cultural experiences. He acknowledges that many of us want to do it right but don't know how. This style guide is presented as part of the solution. It will definitely require integrating into existing style guides or use as a stand-alone resource for us to be successful.

"Working in an appropriate way begins with a clear understanding of how Indigenous Peoples perceive and contextualize their contemporary cultural realities." (Pg 17). It is important not to become overwhelmed with all the in-depth instruction but, like acquiring any new skill, go step by step.

I have to agree with Younging on the importance of recognizing and respecting Indigenous cultural property. Principle 3: Indigenous Literature and Canlit states Indigenous literature is its own category, not a subgroup. Non-Indigenous authors do not have the same artistic license as the unique one of Indigenous authors.

This goes much deeper than words. Collaboration (Principle 6) is critical to success: such as working with Elders. Messages need to be created together.

Indigenous writing insights

Younging clearly outlines what not to do. Inappropriate terminology (Principle 11) to never be used includes brave, red Indian, band, folklore, native, primitive and other terms with an explorer, missionary or anthropology influence. But he also tells us which terms are acceptable.

Principle 18: Inappropriate Possessives lists common offensive phrases we should all avoid: Canada's Indigenous Peoples or the First Peoples of Canada. They imply ownership. A style guide is often a reference tool. But this is more of a cultural, practical, must-do resource.

Indigenous and plain language styles can definitely learn from each other. There's just no arguing: we need them and we must strive to follow them. As we move forward, clarity, collaboration and cultural sensitivity must be our top priorities.

Plain Language and Indigenous Style

As I began my exploration of Indigenous style principles, I was inspired to find a key plain language—Indigenous style connection: focus on and sensitivity to the audience. Plain language is communication that audiences can easily understand, efficiently navigate and effectively act on. But Younging takes it a step further.

Plain language is a process: simply creating grade six reading level content does not make a document plain language. You need audience awareness, reader-sensitive content and clear design, supported by user testing. Younging gets right to the point on rules of Indigenous style and aims for no exceptions. For some, this change in how things are done might seem difficult. But I recommend sticking with it for the rewards, as following the plain language process has given us proven results.

Where plain language and Indigenous style also cross paths is the need for updating style guides, training and processes. Plain language strives to be an accepted and integrated priority but can often be a last–minute addition. Younging takes a much stronger approach, stating if there is a difference between a traditional style guide and Indigenous style, the latter is the only acceptable form.

I look forward to future collaboration between plain language and Indigenous communicators.

How to make Indigenous style work

It may seem overwhelming, as many of us will be learning, or discovering for the first time, a new way to write. With this style guide, you can make much needed changes and become an Indigenous style champion in your organization. But be prepared to commit to a process which will take time and require patience. This guide opens the door to Indigenous writing and publishing standards. Hopefully Younging will open more of these style guide doors for us.

by Kate Harrison Whiteside

Plain Language consultant

RSS Feed

RSS Feed